Most motile protozoans, which are strictly aquatic animals, move by locomotion involving one of three types of appendages: flagella, cilia, or pseudopodia. Cilia and flagella are indistinguishable in that both are flexible filamentous structures containing two central fibrils (very small fibres) surrounded by a ring of nine double fibrils. The peripheral fibrils seem to be the contractile units and the central ones, neuromotor (nervelike) units. Generally, cilia are short and flagella long, although the size ranges of each overlap.

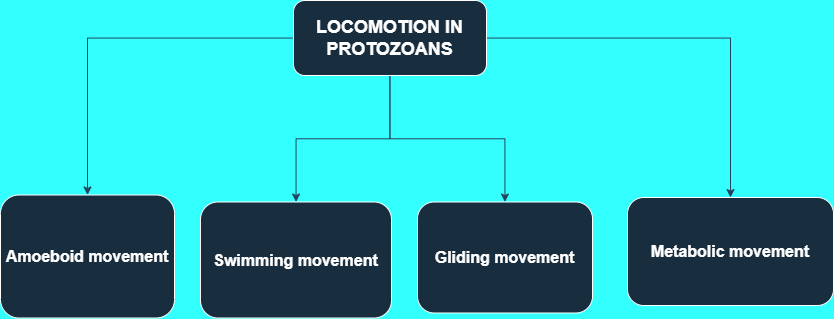

METHODS OF LOCOMOTION IN PROTOZOANS

Basically there are four known methods by which the protozoans move

1. Amoeboid movement

2. Swimming movement

3. Gliding movement

4. Metabolic movement

1. AMOEBOID MOVEMENT

This type of locomotion is also called as pseudopodial locomotion. Here locomotion is brought about by the pseudopodia. It is the characteristic of rhizopod protozoans like Amoeba proteus and Entamoeba histolytica. Also such movement is exhibited by amoeboid cells, macrophages and phagocytic leucocytes like monocytes and neutrophils of metazoans. Various theories have been proposed to explain the amoeboid locomotion.

Name of theory Proposed by

- Contraction theory – Schultuz

- Walking theory – Dellinger

- Rolling movement theory – Jenning

- Surface tension theory – Berthold

- Adhesion theory – Jenning

- Fountain zone theory – Allen

- Folding and unfolding theory – Goldacre and Lorch

- Hydraulic pressure theory – Renoldi and Jaun

- Sol-gel theory – Hyman

Sol Gel theory

Sol Gel theory convincingly explains the mechanism involved in the formation of pseudopodia. This theory, also known as Change in viscosity theory was advocated by Hyman. Later Pantin and Mast explained this theory. According to this theory, the cytoplasm of amoeba can be distinguished into outer ectoplasm/Plasmagel and the inner endoplasm/Plasmosol. The plasmagel which forms the outer layer of the cytoplasm is thick, less in quantity, non-granular, transparent and contractile. The plasmosol which forms the inner layer of the cytoplasm is more in quantity, less viscous, fluid like, more granular and opaque. Due to change in the viscosity, the plasmagel and plasmosol inter-convert and consequently the pseudopodia form and disappear causing the movement of Amoeba. This inter-convertibility of plasmagel and plasmosol is physicochemical change. Gel becomes sol by taking water and sol becomes gel by losing water.

Amoeboid locomotion can be explained in the following steps:

Step 1: Initially Amoeba attaches itself to the solid substratum by the plasma lemma at the temporary anterior end.

Step 2: Then the hyaline layer of the ectoplasm at the anterior end forms a thickened hyaline cap. It is the first stage in the formation of the pseudopodium.

Step 3: Behind the hyaline cap, a point of weakness in the elasticity of plasmagel is formed. Hence the inner plasmosol flows forward, forming a pseudopodium.

Step 4: The plasmosol that flows outward behind the hyaline cap changes its colloidal state from sol to gel and joins the ectoplasm.

Step 5: The outer region of the plasmosol, which is flowing forward undergoes gelation and produces a rigid plasmagel tube. The gelation of plasmosol extends the plasmagel tube forward.

Step 6: Two ends appear in Amoeba at this stage. The anterior end is smooth with the rounded surface which the retractile end also called as Uroid has a wrinkled surface.

Step 7: Around the region of the hyaline cap, an annular region of sol to gel transformation is formed. It is called the zone of gelation. At the uroid end a region where gel transforms into sol is called as zone of solation.

Step 8: Plasmagel at the uroid end changes into sol and flows forward continuously through the gelatinized tube. As the plasmosol flows forward, the pseudopodium elongates further and the body of amoeba moves in that direction. The ectoplasm does not move but grows at the leading tip and is broken down at the uroid end.

Step 9: The gelation at the advancing end and the solation at the trailing end occur simultaneously and at the same rate thus making the forward movement of amoeba continuous.

Step 10: The contraction of the plasmagel at the trailing end causes hydraulic pressure on the sol and makes the plasmosol flow forward continuously in the plasmagel tube.

Step 11: As the pseudopodium advances continuously in the direction of the movement the body of amoeba also moves.

Basis of action of protein molecules: Sol gel theory

Amoeboid locomotion is brought about by the protein molecules (actin and myosin) present in the cytoplasm. Goldacre and Lorsch explained the phenomenon of gelation and solation based on the folding and unfolding of these protein molecules. According to them, the cytoplasm gelates when the protein molecules unfold by losing water and the cytoplasm solates when the protein molecules folds

by absorbing water.

Hence, the proteins in the plasmosol are in folded state and the proteins in the plasmagel are in the unfolded state. This folding and unfolding of the protein molecules lead to the formation of the pseudopodia and thus the amoeboid movement. The energy required for this process is made available from the ATP.

According to the foundation zone theory put forth by Allen, the plasmosol flows forward due to the pulling force caused by the sliding action of the actin molecules over the myosin molecules at the advancing end. This interconvertibility of sol and gel is mainly due to the assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Assembly results in gel formation and the disassembly leads to the sol formation.

2. SWIMMING MOVEMENT

Swimming locomotion in protozoans is caused by the flagella and cilia. Flagella bring about the movement of some parasites in the body fluids of the hosts. As the movement in this case is caused by the beating flagella and cilia are also known as

undulipodia. Depending on the structure involved swimming movement can be of two types namely,

- Flagellar movement

- Ciliary movement

Type 1 swimming movement: Flagellar movement

Most flagellate protozoans possess either one or two flagella extending from the anterior (front) end of the body. Some protozoans, however, have several flagella that may be scattered over the entire body; in such cases, the flagella usually are fused into distinctly separate clusters.

Flagellar movement, or locomotion, occurs as either planar waves, oarlike beating, or three-dimensional waves. All three of these forms of flagellar locomotion consist of contraction waves that pass either from the base to the tip of the flagellum or in the reverse direction to produce forward or backward movement. The planar waves, which occur along a single plane and are similar to a sinusoid

(S-shaped) wave form, tend to be asymmetrical; there is a gradual increase in amplitude (peak of the wave) as the wave passes to the tip of the flagellum. In planar locomotion the motion of the flagella is equivalent to that of the body of an eel as it swims. Although symmetrical planar waves have been observed, they apparently are abnormal, because the locomotion they produce is erratic. Planar waves cause the protozoan to rotate on its longitudinal axis, the path of movement tends to be helical (a spiral), and the direction of movement is opposite

the propagation direction of the wave. In oarlike flagellar movements, which are also planar, the waves tend to be highly

asymmetrical, of greater side to side swing, and the protozoan usually rotates and moves with the flagellum at the forward end. In the three-dimensional wave form of flagellar movement, the motion of the flagella is similar to that of an airplane propeller; i.e., the flagella lash from side to side. The flagellum rotates in a conical configuration, the apex (tip) of which centres on the point at which the flagellum is

attached to the body. Simultaneous with the conical rotation, asymmetrical sinusoidal waves pass from the base to the end of the flagellum. As a result of the flagellar rotation and its changing angle of contact, water is forced backward over the protozoan, which also tends to rotate, and the organism moves forward in the direction of the flagellum. A flagellum pushes the fluid medium at right angles to the surface of its

attachment, by its bending movement. The bending movement of flagellum is made by the sliding of microtubules past each other with the help of dynein arms. The dynein arms show a complex cycle of movement with the energy provided by ATP. These dynein arms attaché to the outer microtubule of an adjacent doublet and pull the neighboring doublet. As the result the doublets slide past each other in

opposite direction. The arms release and attach a little farther on the adjacent doublet and again pull the neighboring doublet. The doublets of the flagellum are physically held in place by the radial spokes and thus the doublets cannot slide past much and their sliding is limited by the radial spokes. Instead the doublets can curve causing a bend in the flagellum and this bending has an important role in the flagellar movement. Flagellum shows the following movements,

Undulation movement:

Undulation from the base to the tip causes pushing force and pushes the organism backwards. Similarly undulation from the tip to the base

causes pulling force and causes the organism to pull forward. Also when the flagellum ends to one side and shows wave like movement from base to tip the organism moves in laterally in opposite direction. Finally when the undulation is spiral, it causes rotation of the organism in the opposite direction and this is called as gyration.

Sidewise lash movement:

The flagellar movement of many organisms is a paddle-like beat or sidewise lash consisting of strokes namely effective stroke and

recovery stroke. Effective stroke-During effective stroke the flagellum becomes rigid and starts bending against the water. This beating in water at right angles to the longitudinal axis of the body causes the organism to move forward. Recovery stroke- During recovery stroke, the flagellum becomes comparatively soft and will be less resistant to the water. This helps the flagellum move backwards and then to the original position. Simple conical gyration movement: In this kind of movement the flagellum turns like a screw. This propelling action pulls the organism forward through the water with a spiral rotation around the axis of movement and gyration on its own.

Type 2 swimming movement: Ciliary movement

Just like the flagellum, the cilium also shows back and forth movements during the locomotion. These back and forth movements of the cilia are also called as effective and recovery strokes respectively. Cilium moves just like a pendulum or a paddle. The cilium moves the water parallel to the surface of its attachment like that of paddle stroke movement. The movement of water is perpendicular to the

longitudinal axis of cilium. Effective stroke: During effective stroke, the cilium bends and beats against water thus bringing the body forward and sending the water backwards. Recovery stroke: During recovery stroke, the cilium comes back to original position by its backward movement without any resistance. protozoa locomotion, cilliary movement,cilia, locomotion, protozoa Cilia shows two types of coordinated rhythms,

- Synchronous rhythm, where in the cilia beast simultaneously in a transverse row.

- Metachronous rhythm, where in cilia beat one after another in a longitudinal row.

The metachronal waves pass from anterior to posterior end. The beating of the cilia can be reversed to move backwards when a Paramoecium

encounters any undesirable object in its path. The ciliary movement is coordinated by infraciliary system though neuromotor center called as motorium present near the cytopharynx in the ciliates like Paramoecium. The infraciliary system together with motorium form neuromotor system which helps in coordination of the beating of the cilia. Ciliary movement is the fastest locomotion in protozoans.

3. GLIDING MOVEMENT

The zigzag movement in the protozoans brought about by the contraction and relaxation of myonemes present below the pellicle in the ectoplasm is called as the gliding movement. The movement by gliding is comparatively small. Myonemes are the contractile fibrils which are similar to the myofibrils. This kind of gliding movement is shown by flagellates, Sporozoans, Cnidospora and some ciliates.

4. METABOLIC MOVEMENT

In protozoans a pellicle is present in the ectoplasm which is composed of proteinaceous strips supported by dorsal and ventral microtubules. In many protozoans these protein strips can slide past one another, causing wriggling motion. This wriggling motion is called as metaboly or metabolic movement. This movement is mainly caused by the change in the shape of the body. This metabolic movement is observed in most of the sporozoans at certain stages of life cycle. These kinds of movement are also referred to as Gregarine movements as this movement is the characteristic of most of the gregarines.